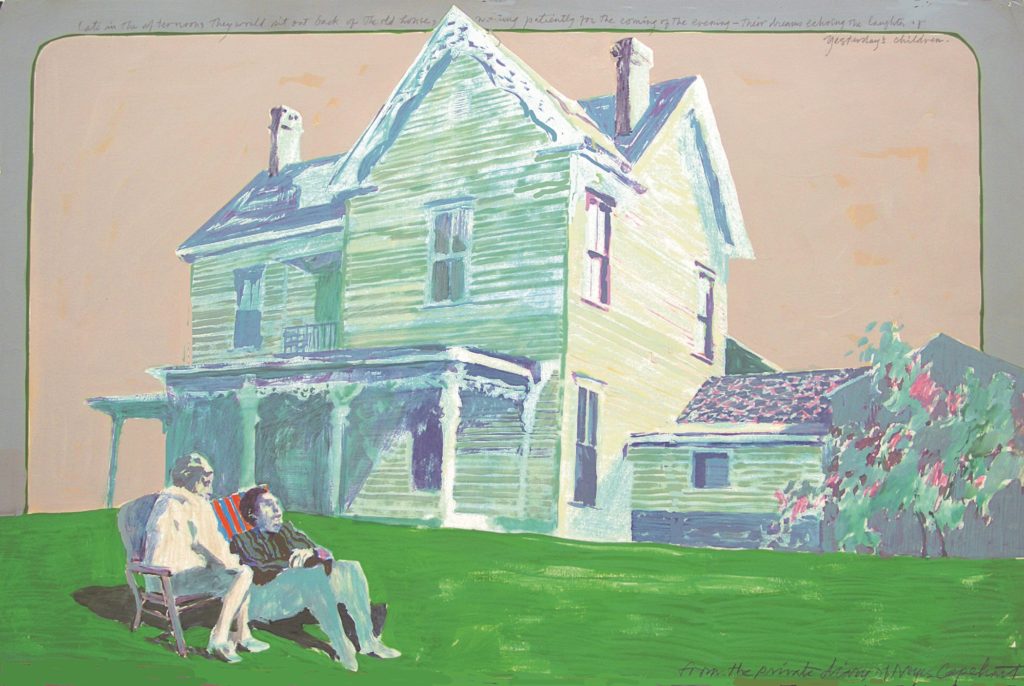

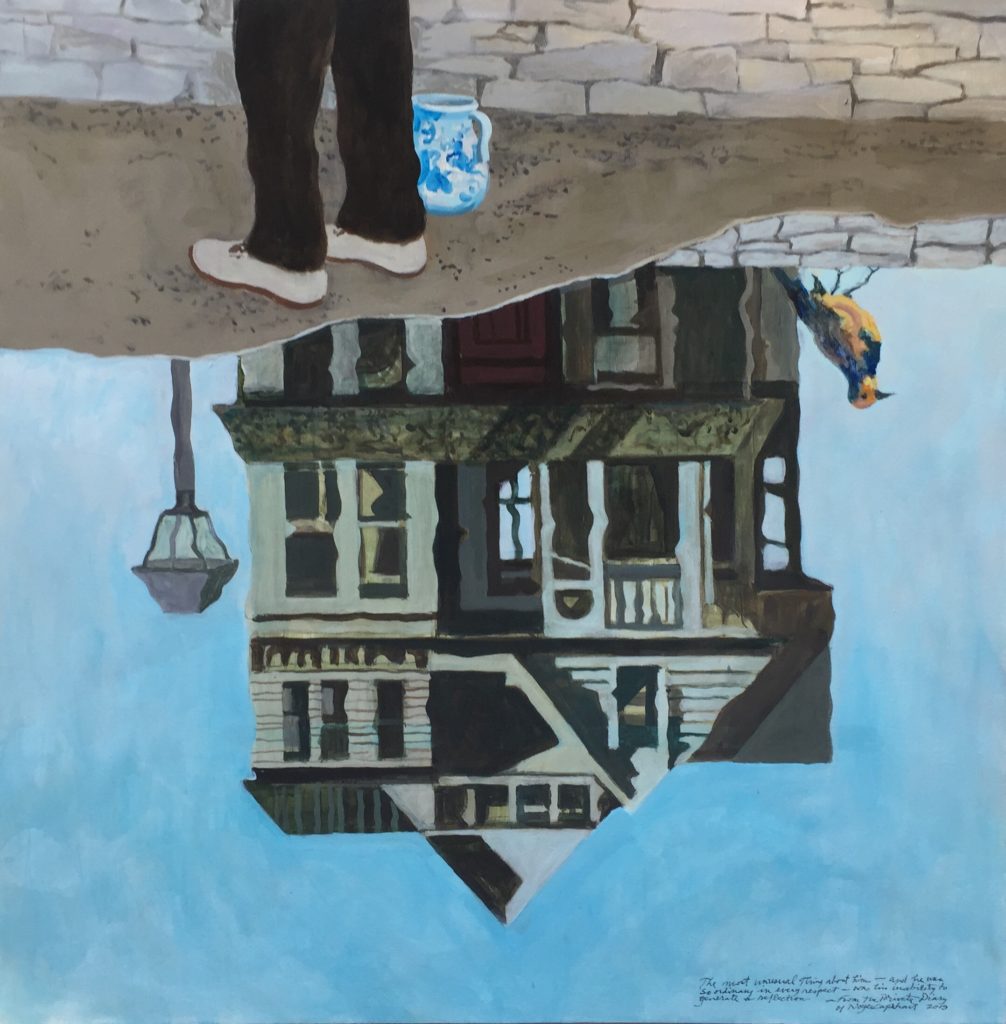

“The most unusual thing about him – and he was so ordinary in every respect – was his inability to generate a reflection.”

– From the Private Diary of Noyes Capehart

As with any painting (or art work of any kind), meaning is usually determined by the person experiencing the work or, as is sometimes the case, left dangling by one who feels less than comfortable in defining or accepting a particularized response. As an artist and writer, I have always taken the position that it is not my intention or responsibility to “spoon feed” a viewer a singular position regarding meaning. For an artist do so, I believe, is to overstep our role with visual dialogue. I want to believe it our job as artists to create pictures that will challenge a viewer to establish some relevant connection. It doesn’t matter that our viewers take away something other than our respective intentions. What matters is that a connection occurs…period.

That said, I will offer a few thoughts about Man of No Reflection: I was not considering the word reflection necessarily in terms of its literal definition. My interests here were more about using the word as a metaphor, a way of suggesting a person void of substance, or merit; a person lacking in such admirable human traits as empathy, compassion, and love and respect for others.

Persons may come to your mind who fit such a dark profile, and you may draw your own conclusions as to whether or not I had a specific person in mind as I approached this picture.

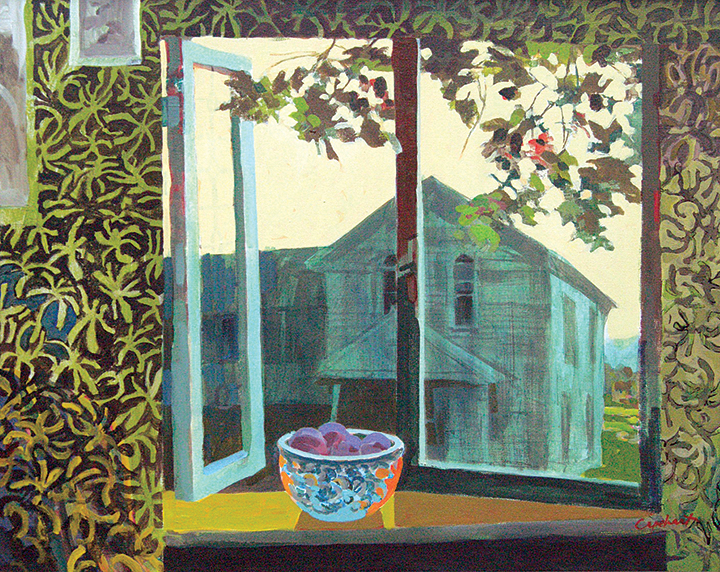

From a compositional perspective – subjective feelings with regard to meaning aside – I felt I had completed this painting when I reached the following state:

I positioned the canvas on our dining room wall and for several days studied it. I began to feel uncomfortable with the harsh contrast between the two vertical legs of the man and the horizontal base of the wall. The transition seemed forced, severe. It was then I incorporated the curved shape of the decorative pitcher. The pitcher not only provided a transitional shape between the vertical and horizontal ones, but it echoed the blue of the sky. The key takeaway here is that a painting probably needs to “simmer” for awhile after before we consider it done. Let it rest. Let it have the time to speak to you. Quite often, we’ll find the need for final adjustments.

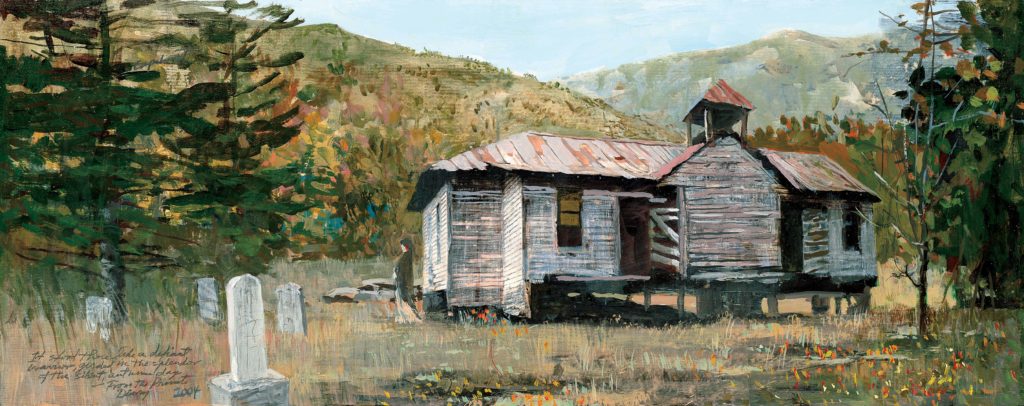

Post script: The inverted image of the house came from a 1994 watercolor, Neglected Houses,shown below.

Man of No Reflections will be one of approximately twenty works in my August 20-September 7, 2019 exhibition at the Art Cellar Gallery in Banner Elk, North Carolina. The reception is scheduled for Sunday, August 24 from 2-6 pm. The public is invited.